“When a Chief Executive Officer is encouraged by his advisors to make deals, he responds much as would a teenager boy who is encouraged by his father to have a normal sex life. It’s not a push he needs.”

Warren Buffett

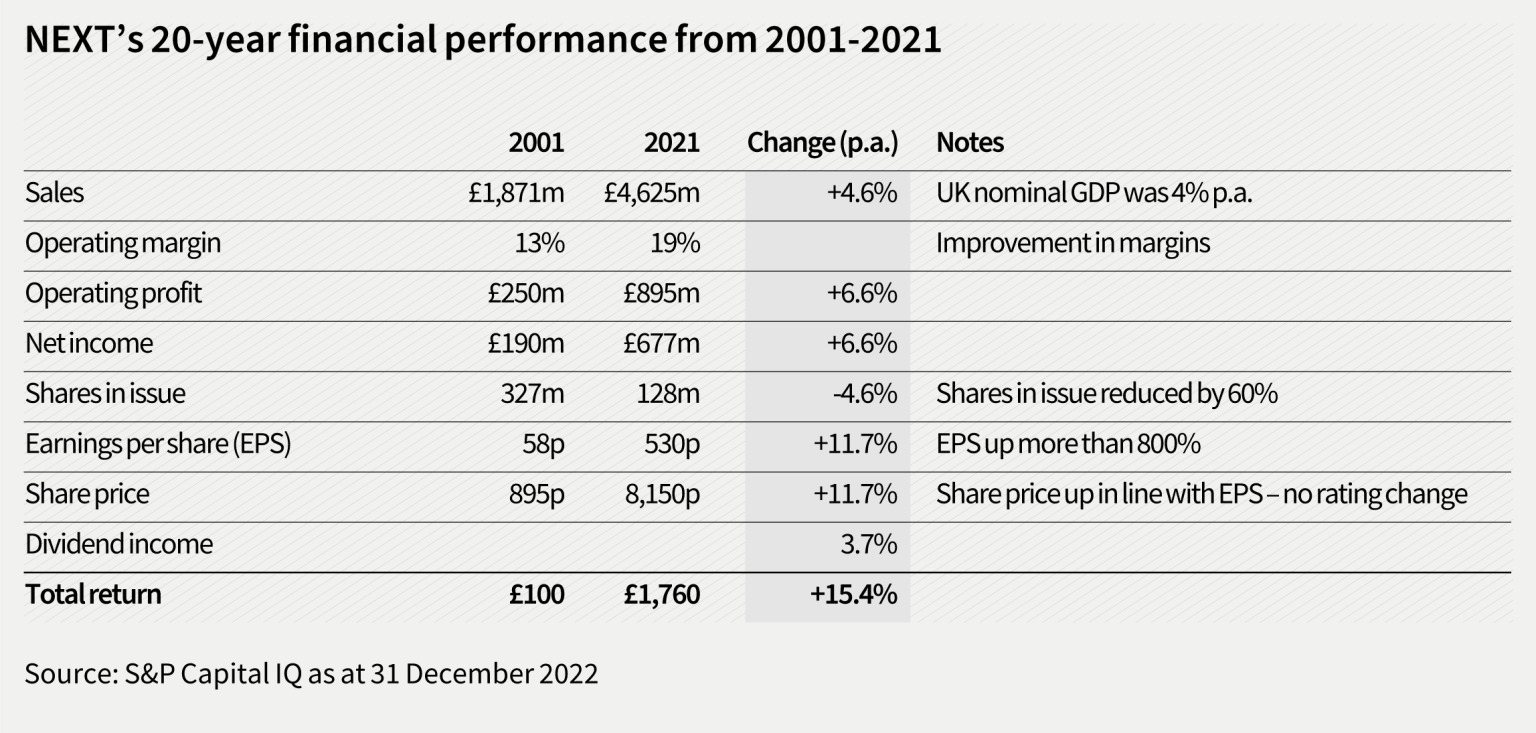

If I told you that there was a UK stock in which if you had invested £100 in 2001, it would now be worth £1,760, which sector would you guess it was in? Technology or maybe biotechnology? What if I told you it was a retailer!?

I suspect you would think that it must have been a small start-up in 2001 that grew through a series of deals like Philip Green’s Arcadia Group or Mike Ashley’s Fraser Group. You would be shocked, therefore, to learn that it had its origins in a gentleman’s tailor called J. Hepworth and Sons which was established in Leeds in 1864, and that it had been around in its current guise since 1981 when Hepworth bought a chain of rainwear shops called Kendall’s and changed its name to…

…NEXT.

I suspect you may now be saying to yourself that you didn’t realise that NEXT’s profits had grown at that phenomenal rate for the last twenty years and the funny thing is, you are right. They didn’t. Sales for the group grew from £1,871m in 2001 to £4,625m in 2021, an annualised growth rate of just 5% per annum, which is less than 1% a year faster than UK nominal GDP through the period.

At which point, you must be thinking that there is an error in my calculations because there is no way that a retailer growing at just above the rate of UK GDP could turn an investment of £100 into £1,760 in just twenty years. So, let me show you how they did it in the table below.

Past performance is not a guide to future returns. No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment.

Whilst sales may have only grown by 4.6% a year, operating leverage and good control of costs meant that operating profits grew by 6.6% per annum, and the company’s operating profit margin expanded from 13% to 19%. The company’s net income (after its interest and tax) also grew by 6.6% per annum, but here is the clever part.

Throughout this period, the company used its surplus cash flow to buy back its own shares, which meant that the shares in issue declined by 60% from 327m to 128m. As a result of this reduced share count, the earnings per share increased from 58p to 530p, which is an annualised growth rate of nearly 12% per annum. In addition, shareholders received an annual dividend equivalent to 3.7% per annum, turning the 11.7% capital return into a total return of 15.4% per annum.

So, what can we as investors learn from this story of success?

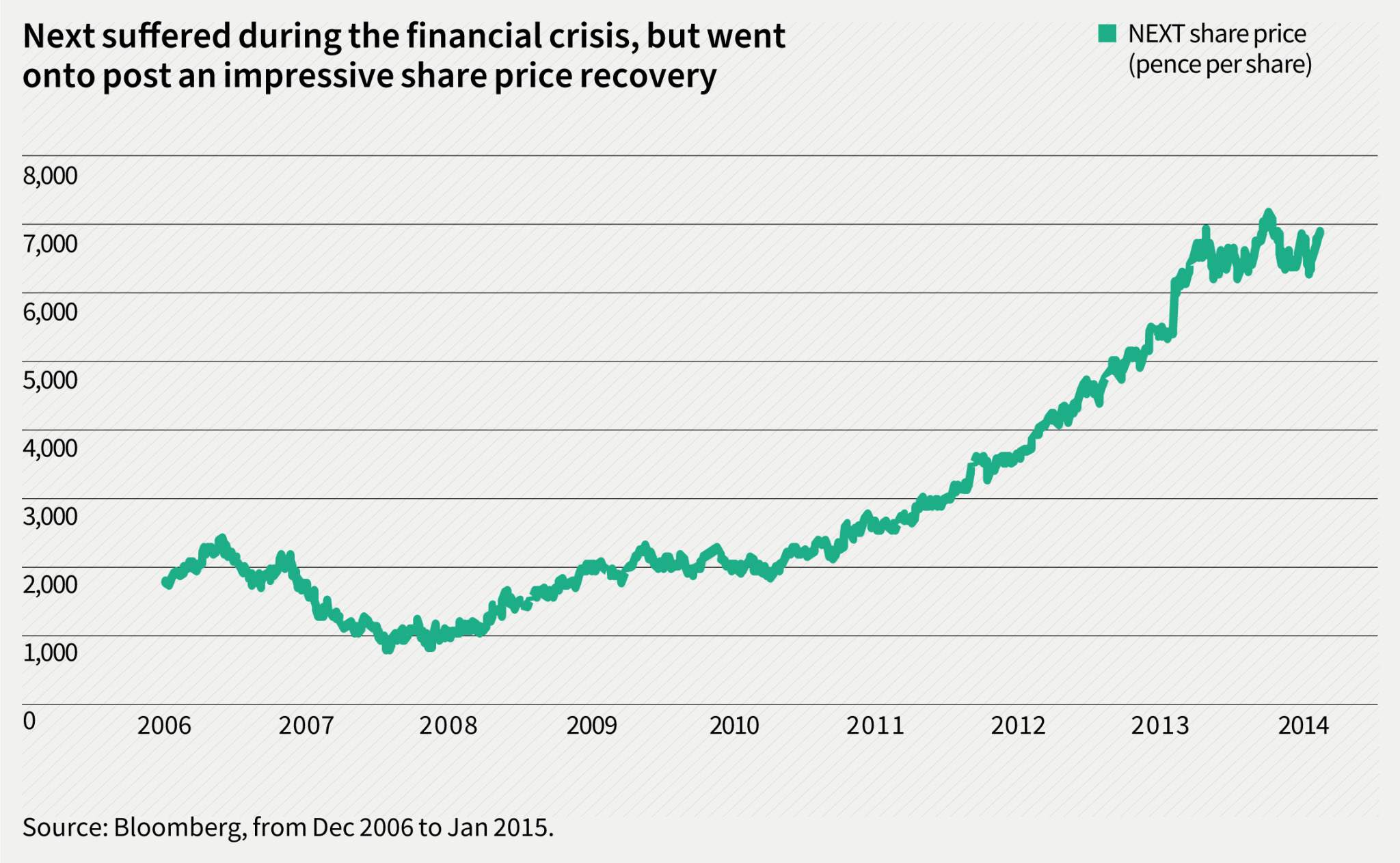

Lesson one: Cyclical stocks can produce attractive long-term returns

On average, NEXT’s sales grew by almost 5% per annum between 2001 and 2021, but NEXT is a cyclical company which suffered during the three economic downturns that occurred during the period (operating profit fell 10% in 2008, 15% in 2016 and 40% in 2020)[1]. Lesson number one is, therefore, that cyclical stocks can produce good long-term returns, and if you buy them during a downturn when the share price is typically depressed, these returns can be significantly enhanced. By way of example, during the global financial crisis, NEXT’s share price fell from £25 to below £10. By 2015 it had recovered to £76, a return of more than 700% from the lows.

The information shown above is for illustrative purposes. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

This lesson is particularly pertinent today, as the share prices of cyclical companies are once again trading at very low valuations, which should be a precursor to a period of good returns when the economic cycle recovers.

Lesson two: Sensible asset allocation is one of the key determinants to long-term returns

The same person, Lord (Simon) Wolfson, has been chief executive of NEXT throughout this entire period, which is remarkable in a world where the average tenure of a FTSE 100 CEO is just under seven years. The outstanding returns to shareholders highlighted above are arguably therefore a function of his astute asset allocation decisions which did not involve making lots of acquisitions (in fact, we believe that the returns were this good because he did not make lots of acquisitions).

In addition, during a period when investment returns were nearly always improved through the use of leverage (ask nearly any buy-to-let landlord), NEXT maintained a strong balance sheet and financed share buybacks through internally generated surplus cash flow.

Finally, shares were only repurchased when they were cheap. Any share buybacks were subject to achieving a minimum 8% equivalent rate of return (ERR)[2]. At times when this hurdle rate could not be cleared, because the shares were not cheap enough, the buyback was simply paused. Thus, the second lesson is that the asset allocation policy of the CEO can be one of the key determinants of long-term returns to a company’s shareholders.

Lesson three: Buying back shares can be a very sensible use of shareholders’ funds

The ‘dividends good, share buybacks bad’ narrative you hear from (mostly income) fund managers, is overly simplistic in our opinion. Sometimes, it makes more sense to use surplus cash flow to buy back shares than to make any alternative asset allocation decision. It all comes down to a company’s judgement of intrinsic value. If a company’s share price is trading below what it considers to be its intrinsic value, buying back its own shares has one of the best risk-return payoffs of all asset allocation decisions, because that company is in a better position than anyone else to estimate its own value.

Warren Buffett opined on this subject in Berkshire Hathaway’s 1984 letter to shareholders:

“When companies with outstanding business and comfortable financial positions find their shares selling far below intrinsic value in the marketplace, no alternative action can benefit shareholders as surely as repurchases.”

By contrast, paying a premium to buy somebody else’s company has one of the worst risk-reward payoffs, since the seller has the information advantage. The only thing worse than this is paying a premium to get into a completely new business area (a folly dubbed ‘diworsification’ by Peter Lynch, legendary fund manager of the Fidelity Magellan fund in his book ‘One Up on Wall Street’).

Why is this relevant to Temple Bar shareholders?

The lessons outlined above are relevant to all investors and lessons two and three are points that we regularly raise with company management teams. More specifically to Temple Bar, as you will know, the portfolio currently has significant exposure to energy and mining companies which are generating prodigious amounts of cash flow as a result of elevated commodity prices. Despite this, the shares of these companies continue to trade on very low multiples of those cash flows. These companies have the ‘nice’ problem of deciding how to most appropriately allocate this cash flow, bearing in mind the interests of their shareholders and other stakeholders. The usual options available to them are to reduce debt, invest, pay dividends, buy back stock or make acquisitions. Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Pay down debt

Most of these energy companies have been able to pay down their debt. For instance, the net debt of Shell has declined from $73bn in 2016 and is forecast to be below $30bn in the coming year[3]. To put this in perspective, free cash flow (after interest, tax and capital expenditure) in 2022 is likely to be around $40bn. This is a positive for investors, because it reduces financial risk and increases the potential for improved shareholder returns in the future.

Invest

The energy companies, in particular, face a real dilemma. Current elevated oil and gas prices would normally be a market signal that demand is outstripping supply, and this would encourage new investment. The usual functioning of the capital cycle has been disrupted, however, by the hostility that the energy companies face from governments with recently announced windfall taxes being an obvious example. The signal this sends to the companies is that they will bear the risk for new investment and keep all the losses if it fails, whilst governments will take away some of the profits if it succeeds. This is a clear disincentive to invest, and it is therefore not surprising that bp, Shell, Total and Harbour Energy have all announced plans to cut North Sea investment.

Pay dividends and buy back shares

With debt at a comfortable level and governments doing their best to discourage new investment, these companies have significant amounts of surplus cash flow that they can allocate (e.g. the $40bn figure for Shell mentioned above). Rather than allowing this cash to build up on their balance sheets earning a low return, the companies have been returning it to shareholders in the form of dividends and share buybacks. Given the importance of sensible asset allocation explained above, we believe this is exactly what they should be doing. Again, using the example of Shell, some analysts are forecasting $20bn of shareholder returns (via a dividend of c.$7.5bn and share buybacks of c. $12.5bn) in 2023.

Acquisitions

When it comes to acquisitions, we will be closely watching what the energy companies do, since our experience tells us that some of the worst investment decisions are made when executives have too much cash sloshing around and their confidence is high.

“Just as work expands to fill available time, corporate projects or acquisitions will materialize to soak up available funds… any business craving of the leader, however foolish, will be quickly supported by detailed rate-of-return and strategic studies prepared by his troops.”

Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway letter to shareholders, 1989

By way of example, mining company Rio Tinto acquired Alcan in 2007 for $38.1bn and by 2013, the company said write-downs relating to the deal had reached an incredible $25bn or two-thirds of the original purchase price. This transaction is a case study in what can go wrong with acquisitions. Firstly, Rio paid a massive 65% premium to the pre-bid share price of Alcan having become embroiled in a bidding war with other mining giants. Secondly, it bought Alcan, a manufacturer of aluminium, at a 20-year peak in aluminium prices. And finally, it financed the deal by increasing its debt from $2.4bn to $46.3bn[4].

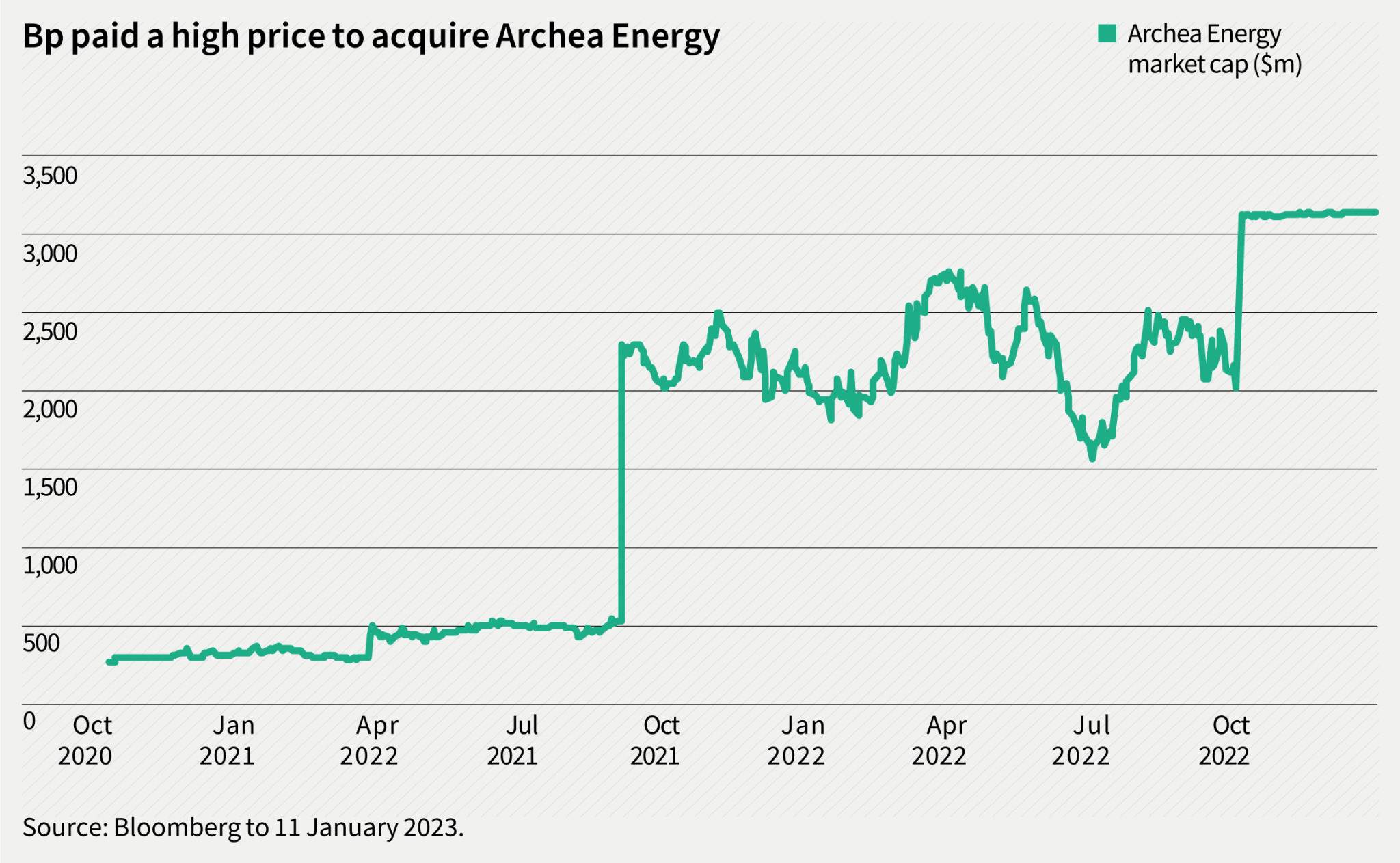

In the absence of investing in new gas production, many energy companies have switched some of their investment to alternative forms of energy. Whilst this might make sense from an environmental perspective, the area is currently very fashionable, meaning that acquisition multiples are high and this tends to make deals much riskier. Bp, for instance, recently acquired a bioenergy company called Archea Energy for $4.1bn including $800m of debt. This represented a 55% premium to the closing share price before the deal was announced.

The information shown above is for illustrative purposes. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

In the twelve-month period to the end of September 2022, Archea had sales of $300m and net income of $100m[5], hence the acquisition multiple was nearly 14x enterprise value to sales and 33x market cap to earnings. Based on the experience of history, the probability of this turning out to be a good deal is low because the price paid is so high, and it has to be seen in the context of bp’s own shares trading on a price to earnings ratio of just 5x. The deal has been justified on aggressive growth projections by the advisors working on the deal who claim that is a multiple of “around four times the expected 2027 EBITDA”,[6].

As usual, Warren Buffett sums up the situation superlatively well:

“Of one thing be certain: if a CEO is enthused about a particularly foolish acquisition, both his internal staff and his outside advisors will come up with whatever projections are needed to justify his stance. Only in fairy tales are emperors told that they are naked.”

Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway letter to shareholders, 1997

Conclusion

Whilst we would caution all CEOs about the risks of acquisitions, we are closely watching those occurring in the energy sector. The combination of abundant capital to finance deals which are being done in new and fashionable areas makes us nervous and we will keep a close watch on how these progress. In our view, Bp’s acquisition of Archea is not large enough to alter the investment case dramatically, but our concern is that larger acquisitions may take place in the sector, which ultimately run the risk of destroying shareholder value.

Needless to say, we will be actively encouraging the management teams of businesses within the Temple Bar portfolio to allocate capital sensibly. Typically, that will mean discouraging acquisitions that can erode shareholder value and supporting buybacks if they can enhance long-term returns.

With the share prices of many incumbent operators trading at such low valuations, the risk-reward of a share buyback looks much better to us than highly-priced acquisitions in new areas. Buying back shares may be significantly less exciting than making big new acquisitions but as the case study of NEXT demonstrates, sometimes boring is good.

[1] Source: Bloomberg

[2] ERR is calculated by dividing the anticipated pre-tax profits by the current market capitalisation

[3] Source: Bloomberg

[4] Source: Bloomberg

[5] Source: Bloomberg

[6] Source: bp

Past performance is not a guide to the future. The price of investments and the income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so.

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Nothing in this document should be construed as advice and is therefore not a recommendation to buy or sell shares. Information contained in this document should not be viewed as indicative of future results. The value of investments can go down as well as up.

This document is issued by RWC Asset Management LLP (Redwheel), in its capacity as the appointed portfolio manager to the Temple Bar Investment Trust Plc. Redwheel, is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the US Securities and Exchange Commission.

Redwheel may act as investment manager or adviser, or otherwise provide services, to more than one product pursuing a similar investment strategy or focus to the product detailed in this document. Redwheel seeks to minimise any conflicts of interest, and endeavours to act at all times in accordance with its legal and regulatory obligations as well as its own policies and codes of conduct.

This article is directed only at professional, institutional, wholesale or qualified investors. The services provided by Redwheel are available only to such persons. It is not intended for distribution to and should not be relied on by any person who would qualify as a retail or individual investor in any jurisdiction or for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.

The information contained herein does not constitute: (i) a binding legal agreement; (ii) legal, regulatory, tax, accounting or other advice; (iii) an offer, recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell shares in any fund, security, commodity, financial instrument or derivative linked to, or otherwise included in a portfolio managed or advised by Redwheel; or (iv) an offer to enter into any other transaction whatsoever (each a Transaction). No representations and/or warranties are made that the information contained herein is either up to date and/or accurate and is not intended to be used or relied upon by any counterparty, investor or any other third party. Redwheel bears no responsibility for your investment research and/or investment decisions and you should consult your own lawyer, accountant, tax adviser or other professional adviser before entering into any Transaction.

How to Invest

The Company’s shares are traded openly on the London Stock Exchange and can be purchased through a stock broker or other financial intermediary.